The Ungrateful Syndrome

- David Langford

- Business, Education, General

- 0 Comments

“Change for the sake of change passes the time.” – Joel Barker

I often hear teachers and administrators complaining that they have given students laptop computers, smart boards, new textbooks, science equipment, language parties, new tardy bells and gym equipment, and the students don’t seem to appreciate any of it. In fact, students frequently abuse these materials — deflating basketballs, vandalizing walls, and scratching equipment. Have we simply bred a generation of apathetic scallywags? Or is there something else going on?

Recently, Trevor, a 4th grade teacher in Australia, became unhappy with results he was seeing in his class. Hoping to change the results, he approached his principal, who told him about a new method of restructuring the classroom. Trevor thought it sounded interesting and spent a year researching the concept. He went to training on the theory and got his team teaching partner, Erwin, to understand and agree to give it a go. The two of them worked hard rearranging the room, getting new furniture, and teaching the students about their new, “dynamic” environment.

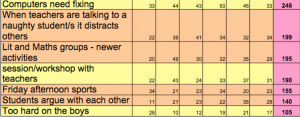

At first, the students were happy enough to do something different. However, within a short time the same problems began to emerge. Math results plummeted, fights broke out, and Trevor returned to his old habit of yelling at students. In doing so, he became a classic example of “The Ungrateful Syndrome.” Fortunately, Trevor had also had some Quality Improvement training, and he decided to use some tools with the students to gather data. He asked the students to complete three Plus/ Delta charts on the topics: Students, Teachers, and Learning.

The results showed Trevor and Erwin that the real problems and opportunities were sitting right in front of them. When they defined and prioritized all the opportunities, they came up with these seven main areas:

- Teachers were too hard on the boys.

- The computers need fixing.

- Newer activities for Literacy and Maths.

- Need Friday afternoon sports.

- The students argue with each other too much.

- More time with teachers.

- When a teacher is disciplining a student it distracts others.

Students then individually used the Nominal Group Technique (NGT) to rate these issues from 1 (least important) to 7 (most important).

After compiling the results of the NGT, they found that the students ranked “fixing the computers” as the most important problem. Still, Trevor did what many teachers do: he shot the messengers. He told the students it was a waste of time and money. He knew they had a few problems with the computers, but he couldn’t imagine it was the most important problem. Still, for the sake of the students, he decided to collect more data over the following two weeks. The results shocked the entire class — they had over 193 problems with the computers in that short period alone.

Humbled, Trevor immediately went to work securing a tech and the support they needed to fix the computers. The result? Grateful students! Instead of messing around with the machines, they treated them with care, and Trevor found that the working machines cut a significant chunk of wasted time out of his day. Perhaps the most important result was that the students felt validated in their opinion, and when Trevor asked them to move on to the next highest problem (his priority), they jumped in with both feet.

The moral of the story is pretty simple. By including students in decisions about resource allocation and management, they have an intrinsic desire to respect new equipment, technology, and schedules. Most importantly, however, it’s a massive trust-building exercise.

David P. Langford President, Langford International, Inc.